Which Of These Famous Renaissance Paintings Was Redone In The Mannerist Style By Jacopo Tintoretto?

| Tintoretto | |

|---|---|

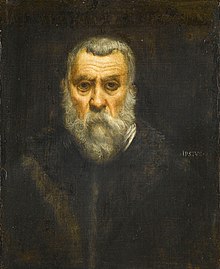

Cocky-portrait, c. 1588 | |

| Built-in | Jacopo Robusti Late September or early October 1518 Venice, Republic of Venice |

| Died | 31 May 1594(1594-05-31) (aged 75) Venice, Republic of Venice |

| Nationality | Venetian |

| Known for | Painting |

| Motility | Renaissance, Mannerism, Venetian School |

Tintoretto ( TIN-tə-RET-oh, Italian: [tintoˈretto], Venetian: [tiŋtoˈɾeto]; built-in Jacopo Robusti;[1] belatedly September or early October 1518[two] – 31 May 1594) was an Italian painter identified with the Venetian schoolhouse. His contemporaries both admired and criticized the speed with which he painted, and the unprecedented disrespect of his brushwork. For his phenomenal energy in painting he was termed Il Furioso ("The Furious"). His work is characterised by his muscular figures, dramatic gestures and bold use of perspective, in the Mannerist way.[3]

Life [edit]

The years of apprenticeship [edit]

House of Tintoretto "Fondamenta dei mori" – Cannaregio – Venice

Tintoretto was born in Venice in 1518. His begetter, Battista, was a dyer, or tintore; hence the son got the nickname of Tintoretto, "little dyer", or "dyer'southward male child".[4] Tintoretto is known to have had at least one sibling, a brother named Domenico, although an unreliable 17th-century account says his siblings numbered 22.[5] The family was believed to take originated from Brescia, in Lombardy, then office of the Republic of Venice. Older studies gave the Tuscan town of Lucca as the origin of the family.

Fiddling is known of Tintoretto's childhood or training. Co-ordinate to his early biographers Carlo Ridolfi (1642) and Marco Boschini (1660), his just formal apprenticeship was in the studio of Titian, who angrily dismissed him after simply a few days—either out of jealousy of so promising a educatee (in Ridolfi's account) or because of a personality clash (in Boschini's version).[6] From this time forrard the human relationship between the 2 artists remained rancorous, despite Tintoretto's continued adoration for Titian. For his office, Titian actively disparaged Tintoretto, as did his adherents.[seven]

Tintoretto sought no further teaching, but studied on his ain account with laborious zeal. According to Ridolfi, he gained some experience by working alongside artisans who decorated piece of furniture with paintings of mythological scenes, and studied anatomy by drawing alive models and dissecting cadavers.[viii] He lived poorly, collecting casts, bas-reliefs, and prints, and practicing with their help. At some fourth dimension, maybe in the 1540s, Tintoretto acquired models of Michelangelo's Dawn, Day, Dusk and Night, which he studied in numerous drawings fabricated from all angles.[9] Now and afterwards he very frequently worked by night also as by solar day. His noble conception of art and his high personal ambition were both evidenced in the inscription which he placed over his studio Il disegno di Michelangelo ed il colorito di Tiziano ("Michelangelo's cartoon and Titian's color").[10]

Early works [edit]

The young painter Andrea Schiavone, iv years Tintoretto's junior, was much in his company. Tintoretto helped Schiavone at no accuse with wall-paintings; and in many subsequent instances he also worked for nothing, and thus succeeded in obtaining commissions.[11] The two earliest mural paintings of Tintoretto—washed, like others, for side by side to no pay—are said to take been Belshazzar's Banquet and a Cavalry Fight. These have both long since perished, as have all his frescoes, early or afterwards. The get-go work of his to attract some considerable notice was a portrait-group of himself and his brother—the latter playing a guitar—with a nocturnal consequence; this has likewise been lost. It was followed by some historical subject, which Titian was candid plenty to praise.[12]

One of Tintoretto'south early pictures still extant is in the church of the Carmine in Venice, the Presentation of Jesus in the Temple (c. 1542); also in S. Benedetto are the Annunciation and Christ with the Woman of Samaria. For the Scuola della Trinità (the scuole or schools of Venice were confraternities, more in the nature of charitable foundations than of educational institutions) he painted iv subjects from Genesis. Ii of these, at present in the Gallerie dell'Accademia in Venice, are Adam and Eve and the Death of Abel, both noble works of high mastery, which indicate that Tintoretto was by this time a consummate painter—one of the few who take attained to the highest eminence in the absenteeism of whatever recorded formal training.[12] Until 2012, The Embarkation of St Helena in the Holy Land was attributed to Schiavone. But new analysis of the work has revealed information technology as one of a series of three paintings by Tintoretto, depicting the legend of St Helena and the Holy Cross. The error was uncovered during work on a project to catalogue continental European oil paintings in the United Kingdom.[13] The Embarkation of St Helena was acquired by the Victoria and Albert Museum in 1865. Its sister paintings, The Discovery of the True Cross and St Helen Testing the True Cantankerous, are held in galleries in the United States.[13]

Saint Mark paintings [edit]

In 1548 Tintoretto was commissioned to paint a large ornamentation for the Scuola di S. Marco: the Miracle of the Slave. Realizing that the commission presented him with a atypical opportunity to establish himself equally a major artist, he took boggling care in arranging the composition for maximum issue. The painting represents the legend of a Christian slave or captive who was to be tortured equally a penalization for some acts of devotion to the evangelist, only was saved by the miraculous intervention of the latter, who shattered the os-breaking and blinding implements which were most to be applied.[12] [xiv] Tintoretto'south conception of the narrative is distinguished by a marked theatricality, unusual color choices, and vigorous execution.[15]

The painting was a triumphant success, despite some detractors. Tintoretto's friend Pietro Aretino praised the piece of work, calling particular attention to the figure of the slave, but warned Tintoretto against hasty execution.[xv] As a outcome of the painting's success, Tintoretto received numerous commissions. For the church of San Rocco he painted Saint Roch Cures the Plaque Victims (1549), one of the first of Tintoretto's many laterali (horizontal paintings). These were large-scale paintings intended for the side walls of Venetian chapels. Knowing that the congregation would view them from an angle, Tintoretto composed the paintings with off-middle perspective so the illusion of depth would be effective when seen from a viewpoint near the terminate of the painting that was closer to the worshippers.[16]

Around 1555 he painted the Assumption of the Virgin, an oil on sheet painting for the church of Santa Maria dei Crociferi.[17] In near 1560, Tintoretto married Faustina de Vescovi, girl of a Venetian nobleman who was the guardian grande of the Scuola Grande di San Marco.[18] [ii] She appears to take been a careful housekeeper, and able to mollify her hubby. He had many children with Faustina, of whom three sons (Domenico, Marco, and Zuan Battista) and iv daughters (Gierolima, Lucrezia, Ottavia, and Laura) survived to machismo.[19] Before his marriage Tintoretto had an additional girl, Marietta Robusti, whose mother is not known. Marietta, like her half-brothers Domenico and Marco, was trained as an artist by Tintoretto.[19]

In 1551, Paolo Veronese arrived in Venice and apace began receiving the prestigious commissions that Tintoretto coveted. Unwilling to be overshadowed by his new rival, Tintoretto approached the leaders of his neighborhood church building, the Madonna dell'Orto, with a proposal to paint for them 2 colossal canvases on a toll only basis.[20] He had already painted the Presentation of the Virgin in the Temple (ca. 1556), one of his major works, for the church; it repeats a subject area that had earlier been painted past Titian, merely in place of Titian'southward classically counterbalanced composition is a startling visual drama of figures bundled on a receding staircase.[21] Tintoretto now intended to create a sensation past painting for the Madonna dell'Orto the two tallest canvases ever painted during the Renaissance.[22] He settled down in a business firm well-nigh the church building, looking over the Fondamenta de Mori, which is still standing.[23]

Depicting the Worship of the Gold Calf and the Concluding Judgment, the 14.5 metres (47.six feet) tall paintings (both ca. 1559–60) were widely admired, and Tintoretto gained a reputation for his power to complete the almost massive projects on a limited budget. Thereafter, Tintoretto habitually competed against rival painters past producing paintings quickly at a low price.[24] In about 1564, Tintoretto painted three additional works for Scuola di S. Marco: the Finding of the body of St Mark, the St Marking's Body Brought to Venice, a St Mark Rescuing a Saracen from Shipwreck.

Scuola di San Rocco [edit]

Between 1565 and 1567, and again from 1575 to 1588, Tintoretto produced a large number of paintings for the walls and ceilings of the Scuola Grande di San Rocco. The subterfuge by which he won the commission has been called "the nigh notorious incident of Tintoretto'due south career".[25] In 1564, four finalists—Tintoretto, Federico Zuccaro, Giuseppe Salviati, and Paolo Veronese—were invited by the Scuola to submit modelli for a ceiling painting on the subject of Saint Roch in Glory to decorate the hall called the Sala dell'Albergo. Instead of a sketch, Tintoretto produced a full-sized painting, secretly installed it in the ceiling, and presented information technology every bit a fait accompli on the day of the competition. Tintoretto so announced that he was offering the painting as a gift—perhaps conscious that a bylaw of the foundation prohibited the rejection of whatever gift.[25]

In 1565, he resumed work at the scuola, painting the Crucifixion, for which a sum of 250 ducats was paid. In 1576 he presented gratis another middle-slice—that for the ceiling of the not bad hall, representing the Plague of Serpents; and in the following year he completed this ceiling with pictures of the Paschal Banquet and Moses striking the Rock accepting whatever pittance the confraternity chose to pay.[26]

Item of Portrait of a Venetian admiral (1570s, National Museum in Warsaw) where the original undercoat shines through the assuming brushstrokes.[27]

The evolution of fast painting techniques chosen prestezza allowed him to produce many works while engaged on large projects and to respond to growing demands from clients.[28] This, and his use of assistants, enabled Tintoretto ultimately to produce a greater number of paintings for the Venetian state than any of his competitors.[29]

Tintoretto next launched out into the painting of the entire scuola and of the adjacent church of San Rocco. In November 1577, he offered to execute the works at the rate of 100 ducats per annum, with three pictures being due in each yr. This proposal was accustomed and was punctually fulfilled, the painter's death alone preventing the execution of some of the ceiling-subjects. The whole sum paid for the scuola throughout was 2,447 ducats. Disregarding some minor performances, the scuola and church incorporate fifty-ii memorable paintings, which may exist described as vast suggestive sketches, with the mastery, but not the deliberate precision, of finished pictures, and adapted for existence looked at in a dusky half-calorie-free. Adam and Eve, the Visitation, the Admiration of the Magi, the Massacre of the Innocents, the Agony in the Garden, Christ before Pilate, Christ carrying His Cross, and (this alone having been marred by restoration) the Assumption of the Virgin are leading examples in the scuola; in the church, Christ Curing the Paralytic.[26]

It was probably in 1560, the year in which he began working in the Scuola di Southward. Rocco, that Tintoretto commenced his numerous paintings in the Doge'south Palace; he so executed there a portrait of the Doge, Girolamo Priuli. Other works (destroyed past a fire in the palace in 1577) succeeded—the Excommunication of Frederick Barbarossa by Pope Alexander III and the Victory of Lepanto.[26]

Later the fire, Tintoretto started afresh, Paolo Veronese being his colleague. In the Sala dell Anticollegio, Tintoretto painted 4 masterpieces—Bacchus, with Ariadne crowned past Venus, the Three Graces and Mercury, Minerva discarding Mars, and the Forge of Vulcan, which were painted for fifty ducats each, excluding materials, c. 1578; in the hall of the senate, Venice, Queen of the Sea (1581–84); in the hall of the higher, the Espousal of St Catherine to Jesus (1581–84); in the Antichiesetta, Saint George, Saint Louis, and the Princess, and St Jerome and St Andrew; in the hall of the great council, nine large compositions, importantly battle-pieces (1581–84); in the Sala dello Scrutinio the Capture of Zara from the Hungarians in 1346 amid a Hurricane of Missiles (1584–87).[30] [26]

Paradise [edit]

The crowning production of Tintoretto's life was the vast Paradise painted for the Doge'south Palace, in size 9.1 by 22.6 metres (29.nine by 74.1 feet), reputed to be the largest painting ever washed upon canvas. While the commission for this huge piece of work was nonetheless pending and unassigned Tintoretto was wont to tell the senators that he had prayed to God that he might be commissioned for it, and so that paradise itself might perchance exist his recompense after death.[26]

Tintoretto competed with several other artists for the prestigious commission. A large sketch of the composition he submitted in 1577 is at present in the Louvre Museum, Paris. In 1583, he painted a 2nd sketch with a different limerick, which is in the Museo Thyssen-Bornemisza, Madrid.[31]

The commission was given jointly to Veronese and Francesco Bassano, but Veronese died in 1588 before starting the work, and the commission was reassigned to Tintoretto.[32] He set his sail in the Scuola della Misericordia and worked indefatigably at the task, making many alterations and doing various heads and costumes direct from life.[26]

When the picture had been nearly completed he took it to its proper place, where it was completed largely past assistants, his son Domenico foremost among them. All Venice applauded the finished work; Ridolfi wrote that "it seemed to anybody that heavenly beatitude had been disclosed to mortal optics."[33] Modern fine art historians accept been less enthusiastic, and have generally considered the Paradise junior in execution to the 2 sketches.[33] Information technology has suffered from neglect, only little from restoration.

Tintoretto was asked to name his own toll, but this he left to the authorities. They tendered a handsome corporeality; he is said to have abated something from it, an incident perhaps more than telling of his lack of greed than earlier cases where he worked for nothing at all.[26]

Death and pupils [edit]

Portrait of Marquis Francesco Gherardini (1568), Ca' Rezzonico Museum in Venice

Afterward the completion of the Paradise Tintoretto rested for a while, and he never undertook any other work of importance, though there is no reason to suppose that his energies were exhausted if he had lived a picayune longer.[26] In 1592 he became a member of the Scuola dei Mercanti.[34]

In 1594, he was seized with severe stomach pains, complicated with fever, that prevented him from sleeping and virtually from eating for a fortnight. He died on 31 May 1594. He was cached in the church of the Madonna dell'Orto by the side of his favorite daughter Marietta, who had died in 1590 at the age of thirty. Tradition suggests that every bit she lay in her last repose, her centre-stricken father had painted her final portrait.[26]

Marietta had herself been a portrait-painter of considerable skill, likewise as a musician, vocalist and instrumentalist, only few of her works are now traceable. As a daughter she used to accompany and assist her father at his work, dressed every bit a boy.[nineteen] Eventually, she married a jeweler, Mario Augusta. In 1866, the grave of the Vescovi—his married woman's family—and Tintoretto was opened, and the remains of ix members of the joint families were plant in it. The grave was so moved to a new location, to the right of the choir.[26]

Tintoretto had very few pupils; his two sons and Maerten de Vos of Antwerp were among them. His son Domenico Tintoretto frequently assisted his father in the preliminary work for neat pictures. He himself painted a multitude of works, many of them of a very large scale. At best, they would exist considered mediocre and, coming from the son of Tintoretto, are disappointing. In any event, he must exist regarded equally a considerable pictorial practitioner in his way.[35] In that location are reflections of Tintoretto to be establish in the Greek painter of the Spanish Renaissance El Greco, who likely saw his works during a stay in Venice.[36]

Personality [edit]

Christ at the Sea of Galilee (c. 1575–1580)

Tintoretto scarcely ever travelled out of Venice.[37] His early biographers write of his intelligence and fierce appetite; according to Carlo Ridolfi, "he was always thinking of ways to make himself known as the most daring painter in the world."[22] He loved all the arts and every bit a youth played the lute and various instruments, some of them of his ain invention, and designed theatrical costumes and properties. He was also well versed in mechanics and mechanical devices. While being a very agreeable companion, for the sake of his work he lived in a mostly retired fashion; fifty-fifty when not painting he habitually stayed in his working room surrounded by casts. Hither he hardly admitted anyone, even intimate friends, and he kept his work methods clandestine, shared merely with his assistants. He was total of pleasant witty sayings, whether to bully personages or to others, but he himself seldom smiled.[35]

Out of doors, his wife made him wear the robe of a Venetian citizen; if it rained she tried to make him wear an outer garment which he resisted. When he left the house, she would as well wrap coin up for him in a handkerchief, expecting a strict accounting on his render. Tintoretto'due south customary answer was that he had spent information technology on alms for the poor or for prisoners.[35]

Tintoretto maintained friendships with many writers and publishers, including Pietro Aretino, who became an important early patron.[38]

Style [edit]

Saint George, Saint Louis, and the Princess (1553)

Tintoretto's style of painting is characterized by bold brushwork and the use of long strokes to define contours and highlights.[39] His paintings emphasize the energy of homo bodies in movement, and ofttimes exploit farthermost foreshortening and perspective furnishings to heighten the drama. Narrative content is conveyed by the gestures and dynamism of the figures rather than by facial expressions.[40]

An agreement is extant showing a plan to finish ii historical paintings—each containing twenty figures, vii being portraits—in a two-month menstruation of time. Sebastiano del Piombo remarked that Tintoretto could paint in two days equally much as himself in two years; Annibale Carracci that Tintoretto was in many of his pictures equal to Titian, in others inferior to Tintoretto. This was the general opinion of the Venetians, who said that he had three pencils—one of gold, the second of argent and the third of atomic number 26.[35]

Tintoretto's pictorial wit is evident in compositions such every bit Saint George, Saint Louis, and the Princess (1553). He subverts the usual portrayal of the discipline, in which Saint George slays the dragon and rescues the princess; here, the princess sits astride the dragon, holding a whip. The result is described by art critic Arthur Danto as having "the edginess of a feminist joke" as "the princess has taken matters into her own hands ... George spreads his arms in a gesture of male helplessness, as his lance lies broken on the ground ...It was evidently painted with a sophisticated Venetian audition in mind."[41]

A comparison of Tintoretto's final The Last Supper—1 of his ix known paintings on the discipline—[42] with Leonardo da Vinci'southward handling of the same subject provides an instructive demonstration of how artistic styles evolved over the course of the Renaissance. Leonardo'south is all classical tranquillity. The disciples radiate abroad from Christ in almost-mathematical symmetry. In the hands of Tintoretto, the same effect becomes dramatic, equally the man figures are joined by angels. A servant is placed in the foreground, mayhap in reference to the Gospel of John 13:fourteen–16. In the restless dynamism of his limerick, his dramatic use of lite, and his emphatic perspective effects, Tintoretto seems a baroque artist ahead of his time.

Tintoretto was Venice'south most prolific painter of portraits during his career.[43] Modern critics have often described his portraits as routine works,[44] although his skill in depicting elderly men, such as Alvise Cornaro (1560/1565), has been widely admired.[45] According to art historians Robert Echols and Frederick Ilchman, the many portraits from Tintoretto's studio that were executed largely by administration accept hampered appreciation of his shorthand portraits which, in precipitous contrast to his narrative works, are understated and somber.[43] Lawrence Gowing considered Tintoretto'due south "smoldering portraits of personalities who seemed consumed by their own burn down" to be his "most irresistible" works.[46]

He painted two self-portraits. In the first (ca. 1546–47; Philadelphia Museum of Art), he presents himself without the trappings of status that were customary in self-portraits that came before. The image'due south informality, the directness of the subject'southward gaze, and the bold brushwork visible throughout were innovative—information technology has been called "the first of many artfully unkempt images of the self that take come downwardly through the centuries."[47] The second self-portrait (ca. 1588; Louvre) is an austerely symmetrical depiction of the aged artist "bleakly contemplating his mortality".[48] Édouard Manet, who painted a copy of information technology, considered it "one of the most beautiful paintings in the world."[49]

Legacy [edit]

In 2013, the Victoria and Albert Museum appear that the painting The Embarkation of St Helena in the Holy Country had been painted by Tintoretto (and not past his gimmicky Andrea Schiavone, as previously thought) as part of a series of three paintings depicting the fable of St Helena And The Holy Cross.[thirteen]

In 2019, honoring the anniversary of the birth of Tintoretto, the National Gallery of Art, Washington, in cooperation with the Gallerie dell'Accademia organized a traveling exhibit, the offset to the United States. The exhibition features nearly 50 paintings and more than than a dozen works on paper spanning the artist's entire career and ranging from regal portraits of Venetian elite to religious and mythological narrative scenes.[50]

Gallery [edit]

-

The Supper at Emmaus (1542 or 1543)

-

-

-

The Origin of the Milky Way (1575)

-

The Flight into Egypt (c. 1582)

Notes [edit]

- ^ According to historian Stefania Mason, the discovery and publication in 2004 of a "fanciful account" in a letter of 1678 to a Spanish art collector from his agent in Venice is responsible for a misconception that Jacopo'southward surname was Comin. "Robusti is the name that appears in his tax declarations" and other official documents. Echols 2018, pp. 39–40, 227.

- ^ a b Bernari and de Vecchi 1970, p. 83.

- ^ Zuffi, Stefano (2004). One 1000 Years of Painting. Milan, Italy: Electa. p. 427.

- ^ Echols 2018, p. 39.

- ^ Echols 2018, pp. 38–twoscore.

- ^ Echols 2018, p. 85.

- ^ Echols 2018, pp. 18, 85.

- ^ Echols 2018, pp. 41, 85.

- ^ Echols 2018, pp. 172–173.

- ^ Nichols, Tom. Tintoretto. Tradition and Identity. Reaktion Books, 1999, p. 14.

- ^ Nichols, Tom. Tintoretto. Tradition and Identity. Reaktion Books, 1999, pp. 103 and 241ff.

- ^ a b c Rossetti 1911, p. 1001.

- ^ a b c "BBC News – Tintoretto painting uncovered at London V&A museum". BBC. 7 June 2013. Retrieved 21 Jan 2014.

- ^ "wga". Wga.hu. Retrieved 21 January 2014.

- ^ a b Echols 2018, p. 7.

- ^ Echols 2018, p. 12.

- ^ Presentazione di Carlo Bernardi (1970). L'opera completa del Tintoretto (in Italian). Milano: Rizzoli. p. 98.

- ^ Echols 2018, p. 53.

- ^ a b c Echols 2018, p. 54.

- ^ Echols 2018, pp. 14–17.

- ^ Echols 2018, p. 15.

- ^ a b Butterfield 2007.

- ^ Nichols, Tom. Tintoretto. Tradition and Identity. Redaktion Books, 1999, p. 101.

- ^ Nichols, T. (2003). "Tintoretto family". Grove Fine art Online.

- ^ a b Echols 2018, p. 21.

- ^ a b c d east f thousand h i j Rossetti 1911, p. 1002.

- ^ Grażyna Bastek. "Admirał młodzieńcem podszyty". Ośrodek Kultury Europejskiej EUROPEUM. Archived from the original on 28 March 2014. Retrieved twenty June 2013.

- ^ Jamie Anderson; Jörg Reckhenrich; Martin Kupp (2011). "Prestezza – A New Mode to Paint". The Fine Art of Success: How Learning Keen Fine art Can Create Great Business. John Wiley & Sons. ISBN978-11-19992-53-0.

- ^ Ilchman, Frederick, and Linda Borean (2009). Titian, Tintoretto, Veronese: Rivals in Renaissance Venice. Surrey: Lund Humphries. p. 45. ISBN 9781848220225.

- ^ Echols 2018, p. 137.

- ^ Echols 2018, pp. xxx, 215.

- ^ Echols 2018, pp. 214–215.

- ^ a b Echols 2018, p. 216.

- ^ Bernari and de Vecchi 1970, p. 84.

- ^ a b c d Rossetti 1911, p. 1003.

- ^ Davies, David, Xavier Bray, and John Huxtable Elliott (2004). El Greco. London: National Gallery. pp. 10, 32. ISBN 1-85709-933-8.

- ^ Nichols, Tom. Tintoretto. Tradition and Identity. Redaktion Books, 1999, p. 13.

- ^ Echols 2018, p. 44.

- ^ Echols 2018, pp. xiii, ten.

- ^ Echols 2018, p. xiii.

- ^ Danto, Arthur C. (16 Apr 2007). "A Mannerist in Madrid". The Nation. pp. 34–36.

- ^ Schjeldahl, Peter (April 1, 2019). "All In: The vicarious thrill of Tintoretto". The New Yorker. p. 77

- ^ a b Echols 2018, p. 145.

- ^ Roberto Longhi called them "unmemorable"; John Pope-Hennessy is described as dismissing them as the piece of work of "a mere 'facepainter'". Echols 2018, p. 238.

- ^ Echols 2018, pp. 156–157.

- ^ Gowing, Lawrence (1987). Paintings in the Louvre New York: Stewart, Tabori & Chang. p. 266. ISBN 1-55670-007-v.

- ^ Echols 2018, p. ii.

- ^ Echols 2018, p. 146.

- ^ Echols 2018, p. 148.

- ^ "Tintoretto: Creative person of Renaissance Venice".

References [edit]

- Bernari, Carlo, and Pierluigi de Vecchi (1970). L'opera completa del Tintoretto. Milano: Rizzoli. OCLC 478839728 (Italian linguistic communication)

- Butterfield, Andrew (26 April 2007). "Brush with Genius". New York Review of Books. NYREV, Inc. 54 (7). Retrieved xviii Apr 2007.

- Echols, Robert (2018). Tintoretto: Artist of Renaissance Venice. Yale University Press. ISBN 9780300230406.

- Nichols, Tom (2015) [1999]. Tintoretto: Tradition and Identity, revised and expanded second edition. London: Reaktion Books ISBN 978 ane 78023 450 2.

- Ridolfi, Carlo (1642). La Vita di Giacopo Robusti (A Life of Tintoretto)

- This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain:Rossetti, William Michael (1911). "Tintoretto, Jacopo Robusti". In Chisholm, Hugh (ed.). Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 26 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Printing. pp. 1001–1003.

External links [edit]

- 52 artworks past or subsequently Tintoretto at the Art U.k. site

- Works at Web Gallery of Fine art, the almost complete gallery of the web

- www.JacopoTintoretto.org 257 works by Tintoretto

- Artcyclopedia – Tintoretto's paintings

- Works and literature on PubHist

- Jacopo Tintoretto. Pictures and Biography

- Tintoretto: Artist of Renaissance Venice, exhibition at National Gallery of Art, March 4 - July 7, 2019

Which Of These Famous Renaissance Paintings Was Redone In The Mannerist Style By Jacopo Tintoretto?,

Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Tintoretto

Posted by: spinellaornat1947.blogspot.com

0 Response to "Which Of These Famous Renaissance Paintings Was Redone In The Mannerist Style By Jacopo Tintoretto?"

Post a Comment